Preface | An Evolving Index of Rhetorical Forms

A Preface: Part II

I. The Rise (and Fall) of Form

Some sentences are remembered for centuries; others, forgotten within seconds. The questions of how has consumed the minds of our greatest writers since the early days of ancient Sumer.

For a long time, thousands and thousands of years, Sumerian equivalents of Shakespeare and Steinbeck hunted for answers instinctually, riding on the backs of reflex and chance, with few tools and little technique, experimenting on the fly with various combinations of substance, syntax, structure and style.

Breakthroughs were rare and rarely spectacular, however, for the demands of statecraft and survival kept writing close to the ground, pragmatic and pedestrian.1 Questions of what dominated the conversation. The grander, loftier questions—questions of how—remained largely unanswered, unfathomed. Yet, against the odds, against the elements, against the obstinacy of cuneiform and clay, the Sumerians—alongside the Egyptians and Assyrians, the Hittites and Canaanites—had laid the foundations for the flipside of the coin. Content was born.

Under the aegis of rhetoric, the study of form would arrive—truly arrive—roughly four thousand years later, during the fifth century B.C.; originally with Corax of Syracuse, a Sicilian statesman, but most famously with the Greeks.2 Drawing a line between logos (the logical content of a work) and lexis (the rhetorical delivery of a work), Aristotle was amongst the first to dichotomize content and form. It was a dichotomy further explored and entrenched by Roman rhetoricians, such as Quintilian, who wrote extensively on the difference between res (things or substance) and verba (expression or style).3

For the next two thousand years, content and form would evolve like two rivalrous hemispheres of a single cerebellum, grappling for the foregrounds of consciousness and culture.

From the twelfth to the fourteenth century, as Scholastic philosophy gave rise to academic bureaucracy, lexis would fall out of sight, obscured by the glorification of logos. Between the fifteenth and seventeenth century, as Scholasticism ran out of minutiae, the upstarts of the Renaissance would set the stage for a triumphant return of form, though at no compromise to content—a rare moment of equipoise, pure synergy, which fostered many of the greatest artworks ever to grace our senses. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, as the Romantic Period gave way to the Victorian Era, content and form would rise and fall within a normal, fruitful range. From the twentieth century to today, however, as modernism has given way to postmodernism, as the churn of culture has reached historical highs, Babylonian highs, the glorification of content has taken a deific turn—a period of superstructural glitz, which has rather eclipsed the substructure of form.

Forgotten, but not lost.

II. The Ruins (and Reconstruction) of Rhetoric

According to legend, the art of memory—ars memoriae—began with Simonides of Ceos, a Greek poet, who lived sometime around 500 B.C. One fateless evening, the hall of a grand banquet collapsed, burying many of the guests beneath the rubble. Simonides, one of the few survivors, reconstructed the entire seating-plan from memory, so that families could uncover the bodies of their loved ones.

From then on, spurred by the likes of Cicero and the anonymous author of Ad Herennium, the tradition of ars memoriae would blossom to become what Francis Yates has hailed as one of the great nerve centres of the European tradition.4

In the twenty-first century, the tradition of ars rhetorica—along with ars forma more broadly—could urgently use a Simonides or two. Luckily for us moderns, however, the reconstruction of ars forma requires no Herculean feat of memory, but merely a renewed sense of history and humility—a “standing back,” to borrow the wording of Iain McGilchrist5—so that, as we sift through the fresh rubble of content, we may slowly come to recognize and recombine the scattered shards of form.

So, the conditions of our century echo the preconditions of the fourteenth—a century defined by dead horses and dead ends, artistic and otherwise, which soon began sowing the seeds for a golden regeneration.

The seeds did not sow overnight, however.

Contrary to the mythos, the Renaissance was less a time of unbridled originality than one of reverential imitation and iteration; a time of retracing the footsteps of masters past. Indeed, so dedicated were students of the Renaissance to the remarriage of content and form, university notebooks were often bisected accordingly; not only so that Shakespeare and company could better analyze the what and how in theory, but better synthesize the pair in practice—pouring new wine into old bottles, old wine into new.

Four hundred years from the heights of the Renaissance, the hour has long past for a second renewal of vows; a Renaissance 2.0. The Index that follows constitutes a humble attempt to bring, not the Renaissance, but the Renaissance notebook back to life.

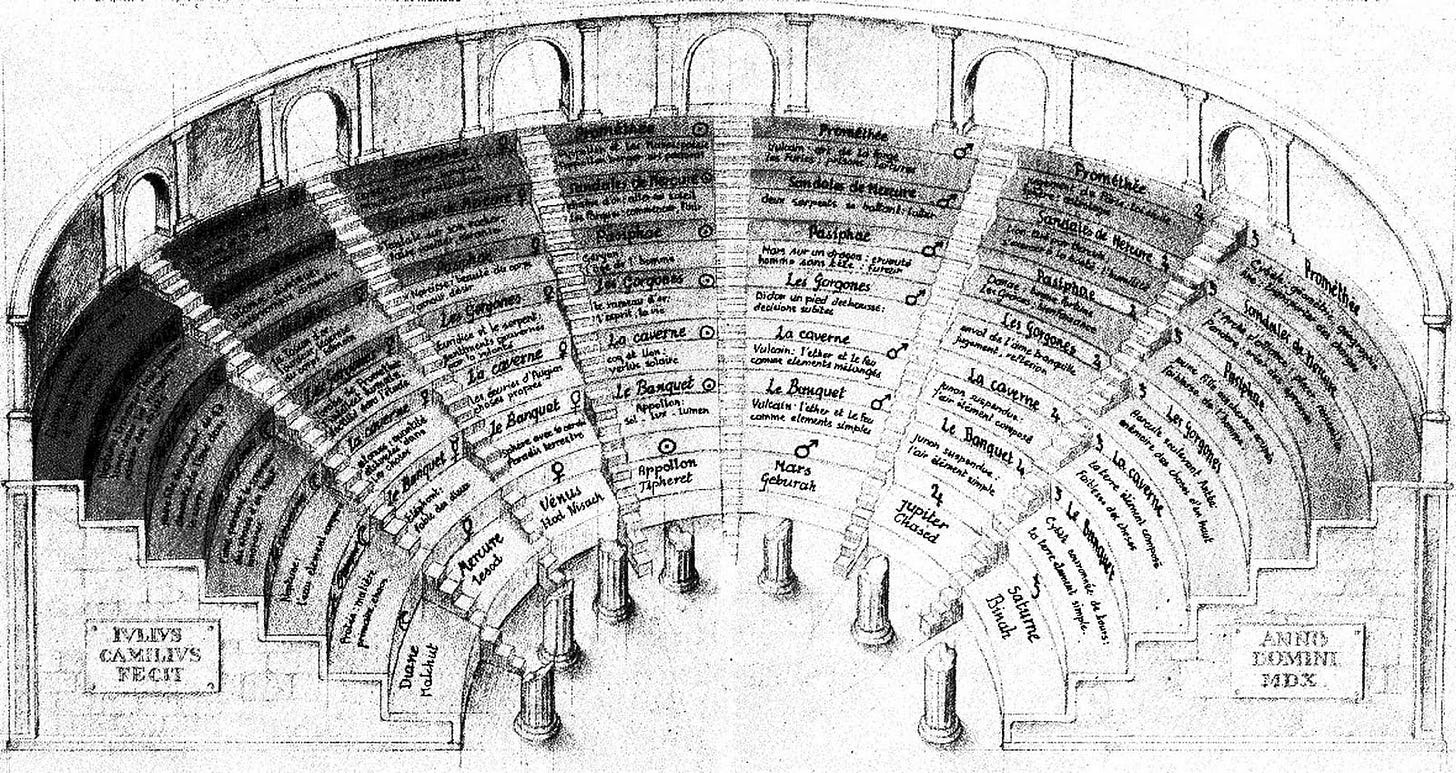

In the spirit of form, let us envisage the Index as a cathedral with five wings, each dedicated to a principle of architecture: Symmetry, Continuity, Hierarchy, Parity and Asymmetry. Within each wing, one can find a number of rooms, each dedicated to a rhetorical form and furnished with a descriptions and two examples.

If you see anything amiss, please leave a comment below.

III. The Index

Symmetry

Chiasmus: a rhetorical form wherein words or grammatical structures are reversed and repeated, amounting to an ABBA pattern.

“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

“We do not get good laws to restrain bad people, we get good people to restrain bad laws.”

Isocolon: a rhetorical form wherein two or more clauses of similar structure and length are placed in parallel; colonnade-esque.

“Veni, Vidi, Vici.”

— Julius Caesar, “Speech to the Roman Senate” (46 BC)

“They who bow to the enemy abroad, will not be of power to subdue the conspirator at home.”

— Edmund Burke, Letters On a Regicide Peace (1796)

Antithesis: a rhetorical form wherein contrasting words or phrases are juxtaposed in parallelistic fashion.

“We notice things that don't work. We don't notice things that do.”

— Douglas Adams, The Salmon of Doubt (2002)

“To err is human; to forgive divine.”

— Alexander Pope, An Essay on Criticism (1711)

Epanalepsis: a rhetorical form wherein the beginning of the clause reappears at the end—a sense of circularity.

“Man’s inhumanity to man.”

— Robert Burns, "Man was Made to Mourn” (1786)

“Nothing comes from nothing.”

— Lucretius, On the Nature of Things (c. 60 BC)

Anaphora: a rhetorical form wherein a sequences of clauses begin with the same word or phrase.

“By his manner, his looks, his voice, when he strikes you with insult, when he strikes you like an enemy, when he strikes you with his knuckles, when he strikes you like a slave.”

— Longinus, On the Sublime (c. 100 BC)

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness…”

— Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

Epistrophe: a rhetorical form wherein a sequence of clauses end with the same word or phrase.

“Wherever they’s a fight so hungry people can eat, I’ll be there. Wherever they’s a cop beatin’ up a guy, I’ll be there… An’ when our folk eat the stuff they raise an’ live in the houses they build—why, I’ll be there.”

— John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath (1939)

“…that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

— Abraham Lincoln, “Gettysburg Address” (1863)

Symploce: a rhetorical form wherein a sequences of clauses begin and end with the same word or phrase.

“The madman is not the man who has lost his reason. The madman is the man who has lost everything except his reason.”

— G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy (1908)

“Most true that though She hated, I would love!

Most true that dearest life shall end with love.”— Bartholomew Griffin, “Sonnet LXII” (1596)

Anadiplosis: a rhetorical form wherein the end of one phrase reappears at the beginning of the next, amounting to an ABBC pattern.

“Mine be thy love, and thy love’s use their treasure.”

—William Shakespeare, “Sonnet 20” (1609)

“The years to come seemed waste of breath,

A waste of breath the years behind.”

— William Butler Yeats, “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” (1919)

Diacope: a rhetorical form wherein a word or phrase is repeated after a brief interruption.

“To be, or not to be, that is the question”

— William Shakespeare, Hamlet (c. 1601)

“Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

— J. Epstein, P. Epstein & H. Koch, Casablanca (1942)

Epizeuxis: a rhetorical form wherein a word or phrase is repeated without interruption.

“Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

— Dylan Thomas, “Do not go gentle into that good night” (1951)

“The horror, the horror.”

— Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899)

Antanaclasis: a rhetorical form wherein words or phrases are repeated to emphasize a deeper or different meaning.

“Ahab is forever Ahab, man.”

— Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

“I do live by the church; for I do live at my house, and my house doth stand by the church.”

— William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night (1623)

Polyptoton: a rhetorical form wherein words derived from the same root are repeated in successive clauses.

“The Greeks are strong, and skilful to their strength,

Fierce to their skill, and to their fierceness valiant.”

— William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida (1609)

“Nothing you can do that can’t be done,

Nothing you can sing that can’t be sung.”

— The Beatles, “All You Need Is Love” (1967)

Alliteration: a rhetorical form wherein the first letter or letters of a word are conspicuously repeated.

“With a good conscience our only sure reward, with history the final judge of our deeds, let us go forth to lead the land we love, asking His blessing and His help.”

— John F. Kennedy, “Inaugural Address” (1961)

“The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free.”

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798)

Homoioteleuton: a rhetorical form wherein the ending of a word becomes a refrain.

“You dare to act dishonourably, you strive to talk despicably; you live hatefully, you sin zealously, you speak offensively.”

— Ad Herennium (c. 80 BC)

“The cheaper the crook, the gaudier the patter.”

— Dashiell Hammett, The Maltese Falcon (1930)

Continuity

Parataxis: a rhetorical form wherein clauses are placed on equal terms, none subordinate to the other.

“I needed a drink, I needed a lot of life insurance, I needed a vacation, I needed a home in the country.”

— Raymond Chandler, Farewell, My Lovely (1940)

“Nick was happy as he crawled inside the tent. He had not been unhappy all day. This was different though. Now things were done. There had been this to do. Now it was done. It had been a hard trip. He was very tired. That was done.”

— Ernest Hemingway, “Big Two-Hearted River” (1925)

Asyndeton: a rhetorical form wherein coordinating conjunctions—and, or, but, et cetera—are omitted.

“Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructors in eloquence and wisdom.”

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, The American Scholar (1837)

“There we meet the slime of hypocrisy, the varnish of courts, the cant of pedantry, the cobwebs of the law, the iron hand of power.”

— William Hazlitt, The Spirit of the Age (1825)

Hypozeuxis: a rhetorical form wherein every clause boasts a subject and verb.

“The grass withereth, the flower fadeth: but the word of our God shall stand for ever.”

— Isaiah 40:8

“The Republicans filibustered, the Democrats snored, and the independents complained.”

— Gideon Burton, Silva Rhetoricae (2007)

Zeugma: a rhetorical form wherein one word—often a verb—modifies two other words.

“He carried a strobe light and the responsibility for the lives of his men.”

— Tim O'Brien, The Things They Carried (1990)

“You held your breath,

And the door for me.”

— Alanis Morissette, “Head Over Heels” (1995)

Schesis Onomaton: a rhetorical form wherein verbs are omitted entirely.

“A man faithful in friendship, prudent in counsels, virtuous in conversation, gentle in communication, learned in all liberal sciences, eloquent in utterance, comely in gesture, an enemy to naughtiness, and a lover of all virtue and godliness.”

— George Peacham, The Garden of Eloquence (1577)

“Paris with the big charcoal braziers outside the cafes, glowing red.”

— Ernest Hemingway, “Christmas on the Roof of the World” (1923)

Hypotaxis: a rhetorical form wherein clauses are placed on unequal terms, subordinate to the main clause.

“While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of someone gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.”

— Edgar Allan Poe, “The Raven” (1845)

“She was now formidable to behold, and it was only in silence, looking up from their plates, after she had spoken so severely about Charles Tansley, that her daughters, Prue, Nancy, Rose—could sport with infidel ideas which they had brewed for themselves of a life different from hers.”

— Virginia Woolf, To the Lighthouse (1927)

Polysyndeton: a rhetorical form wherein the same conjunction repeats throughout a clause or sequence thereof.

“I said, ‘Who killed him?’ and he said ‘I don’t know who killed him, but he’s dead all right,’ and it was dark and there was water standing in the street and no lights or windows broke and boats all up in the town and trees blown down and everything all blown.”

— Ernest Hemingway, “After the Storm” (1933)

“If there be cords, or knives, or poison, or fire, or suffocating streams, I’ll not endure it.”

— William Shakespeare, Othello (1603)

Hendiadys: a rhetorical form wherein the adjective-noun couplet is separated by a conjunction for emphasis.

“The heaviness and guilt within my bosom takes off my manhood.”

— William Shakespeare, Cymbeline (1611)

“Elwood: What kind of music do you usually have here?

Claire: Oh, we got both kinds. We got country and western.”

— Dan Aykroyd & John Landis, The Blues Brothers (1980)

Iambic: a rhetorical form wherein, metrically speaking, one unstressed syllable is followed by one stressed syllable: te-Tum.

“It’s like the new edition of an old book that one has been fond of—revised and amended, brought up to date, but not quite the thing one knew and loved.”

— Henry James, The Ambassadors (1903)

“This frightful business is now unfolding day by day before our eyes.”

— Winston Churchill, “Radio Broadcast, 24 August” (1941)

Trochaic: a rhetorical form wherein, metrically speaking, one stressed syllable is followed by one unstressed syllable: Tum-te.

“Keep thy tongue from evil, and thy lips from speaking guile.”

— Psalm 34:13

“One fact, however, was striking, and fell in with the impression of his natural tiger character, that his face wore at all times a bloodless ghastly pallor.”

— Thomas de Quincey, The Note Book of an English Opium Eater (1855)

Anapestic: a rhetorical form wherein, metrically speaking, two unstressed syllables are followed by one stressed syllable: te-te-Tum.

“Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art.”

— Henry James, “The Middle Years” (1909)

“Never dream with thy hand on the helm!”

— Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

Dactylic: a rhetorical form wherein, metrically speaking, one stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed syllables: Tum-te-te.

“Kings will be tyrants from policy, when subjects are rebels from principle.”

— Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

“I am cast upon a horrible, desolate island, void of all hope of recovery.”

— Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1719)

Hierarchy

Appositio: a rhetorical form wherein a latter phrase further elucidates the former.

“Gussie, a glutton for punishment, stared at himself in the mirror”

— P.G. Wodehouse, Right Ho, Jeeves (1934)

“The sidewalk just outside the Casino was strewn with discarded tickets, the chaff of wasted hope.”

— Jonathan Lethem, Motherless Brooklyn (1999)

Accumulatio: a rhetorical form wherein a general clause is expounded upon and enumerated by particulars.

“I’m a modern man, digital and smoke-free;

a man for the millennium.

A diversified, multi-cultural, post-modern deconstructionist;

politically, anatomically and ecologically incorrect.”

— George Carlin, When Will Jesus Bring the Pork Chops? (2004)

“He is the betrayer of his own self-respect, and the waylayer of the self-respect of others; covetous, intemperate, irascible, arrogant; disloyal to his parents, ungrateful to his friends, troublesome to his kin; insulting to his betters, disdainful of his equals and mates, cruel to his inferiors; in short, he is intolerable to everyone.”

— Ad Herennium (c. 80 BC)

Acceleration: a rhetorical form wherein parallel clauses shorten towards the end.

“Marriage is to me apostasy, profanation of the sanctuary of my soul, violation of my manhood, sale of my birthright, shameful surrender, ignominious capitulation.”

— George Bernard Shaw, Man and Superman (1905)

“Eager faces strained round pillars and corners, to get a sight of him; spectators in back rows stood up, not to miss a hair of him; people on the floor of the court, laid their hands on the shoulders of the people before them, to help themselves, at anybody’s cost, to a view of him.”

— Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

Auxesis: a rhetorical form wherein words or clauses are placed in a climactic order.

“Look! Up in the sky! It’s a bird… It’s a plane… It’s Superman!”

— Whitney Ellsworth & Robert Maxwell, The Adventures of Superman (1952)

“Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.”— Edgar Allan Poe, “The Raven” (1845)

Catacosmesis: a rhetorical form wherein words or phrases are placed in anticlimactic or chronological order.

“The holy passion of Friendship is of so sweet and steady and loyal and enduring a nature that it will last through a whole lifetime, if not asked to lend money.”

— Mark Twain, Pudd’nhead Wilson (1894)

“There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.

— H. L. Mencken, Prejudices: Second Series (1920)

Dirimens Copulatio: a rhetorical form wherein a negative subordinate clause precedes and amplifies an affirmative main clause.

“The real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing in the right place, but, far more difficult still, to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.”

— Lady Dorothy Nevill, Under Five Reigns (1910)

“This poor girl shouldn’t just tell that guy to go jump in a lake, she ought to slash all four of his car tires.”

— Jodi Picoult, House Rules (2010)

Parity

Simile: a rhetorical form wherein one thing is compared to another.

X is like Y.

“She dealt with moral problems as a cleaver deals with meat.”

— James Joyce, Dubliners (1914)

“The cafe was like a battleship stripped for action.”

— Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises (1926)

Metaphor: a rhetorical form wherein one thing is superimposed on another.

X is Y.

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

— William Shakespeare, As You Like It (1623)

“‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,

That perches in the soul.”

— Emily Dickinson, “Hope Is the Thing with Feathers” (1891)

Metonymy: a rhetorical form wherein a related word stands in for the thing itself.

“Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears.“

— William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar (1599)

“The pen is mightier than the sword.”

— Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Cardinal Richelieu (1839)

Metalepsis: a rhetorical form wherein a word stands in for a metonymy which stands in for the thing itself—a double metonymy.

“Therefore came they under the shadow of my roof.”

— Genesis 19:8

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?”

— Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus (1604)

Synecdoche: a rhetorical form wherein a part stands in for the whole.

“‘He shall think differently,’ the musketeer threatened, ‘When he feels the point of my steel.’”

— Alexandre Dumas, The Three Musketeers (1844)

“Take thy face hence.”

— William Shakespeare, Macbeth (1623)

Merism: a rhetorical form wherein two contrasting parts stand in for the whole.

“There is a working class—strong and happy—among both rich and poor.”

— John Ruskin, The Crown of Wild Olive (1866)

“Most people, including most academics, are confusing mixtures. They are moral and immoral, kind and cruel, smart and stupid—yes, academics are often smart and stupid, and this may not be sufficiently recognized by the laity.”

— Richard A. Posner, Public Intellectuals (2001)

Prosopopoeia: a rhetorical form wherein a nonhuman element is personified.

“The farm buildings huddled like the clinging aphids on the mountain skirts, crouched low to the ground as though the wind might blow them into the sea.”

— John Steinbeck, “Flight” (1938)

“Once there was a tree

And she loved little boy.”

— Shel Silverstein, The Giving Tree (1964)

Synaesthesia: a rhetorical form wherein one sense is described in terms of another.

“Thrust me back thither where the sun is silent.”

— Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy (1321)

“As the conductor waved his arms, he molded the air like handfuls of soft clay, and the musicians carefully followed his every direction.

‘What are they playing?’ asked Tock, looking up inquisitively at Alec.

‘The sunset, of course. They play it every evening about this time.’”

— Norton Juster, The Phantom Tollbooth (1961)

Asymmetry

Ellipsis: a rhetorical form wherein words are omitted, but implied.

“‘Did he … peacefully?’ she asked.

‘Oh, quite peacefully, ma’am,’ said Eliza.”

— James Joyce, Dubliners (1914)

“It often happens that the sicker man is the nurse to the sounder.”

— Henry David Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1841)

Enallage: a rhetorical form wherein conventional syntax is deliberately subverted.

“…the manager’s boy put his insolent black head in the doorway, and said in a tone of scathing contempt—‘Mistah Kurtz—he dead.’”

— Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness (1899)

“Think different.”

— Craig Tanimoto, art director at Apple (1997)

Hypallage: a rhetorical form wherein words are swapped around syntactically.

“Come stay with me and dine not.

Darksome wandering by the solitary night.”

— Angel Day, The English Secretary (1599)

“The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen.”

— William Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1600)

Hyperbaton: a rhetorical form wherein the conventional word order is inverted.

“Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall.”

— William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure (1604)

“One swallow does not a summer make.”

— Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics (c. 340 BC)

Prolepsis: a rhetorical form wherein the predicate prefigures the subject.

“They fuck you up, your mom and dad.”

— Philip Larkin, “This Be the Verse” (1971)

“It’s perfectly natural, prolepsis.”

— Mark Forsyth, The Elements of Eloquence (2013)

Anacoluthon: a rhetorical form wherein the syntax is abruptly interrupted.

“I will have such revenges on you both,

That all the world shall―I will do such things,

What they are, yet I know not.”— William Shakespeare, King Lear (1606)

“If thou beest he; but O how fallen! How changed.”

— John Milton, Paradise Lost (1667)

Tmesis: a rhetorical form wherein a word or phrase is interrupted by another word.

“…he got the formula off a barman in Marrakesh or some-bloody-where.”

— Kingsley Amis, Take a Girl Like You (1960)

“If on the first, how heinous e’er it be,

To win thy after-love I pardon thee.”— William Shakespeare, Richard II (1595)

Metanoia: a rhetorical form wherein a word or phrase is retracted, then restated emphatically.

“You might have heard a pin fall—a pin! a feather—as he described the cruelties inflicted on muffin boys by their masters.”

— Charles Dickens, Nicholas Nickleby (1839)

“It was Gatsby’s mansion. Or rather, as I did not yet know Mr. Gatsby, it was a mansion inhabited by a gentleman of that name.”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925)

Catachresis: a rhetorical form wherein words are semantically misused or misplaced.

“Tis deepest winter in Lord Timon’s purse.”

— William Shakespeare, Timon of Athens (1606)

“Dance me to the wedding now, dance me on and on

Dance me very tenderly and dance me very long

We’re both of us beneath our love, we’re both of us above

Dance me to the end of love.”— Leonard Cohen, “Dance Me to the End of Love” (1984)

Anthimeria: a rhetorical form wherein a word or phrase performs an unorthodox grammatical function—often a noun performing as a verb.

“When the rain came to wet me once, and the wind to make me chatter, when the thunder would not peace at my bidding—there I found ‘em.”

— William Shakespeare, King Lear (1606)

“Calvin: I like to verb words.

Hobbes: What?

Calvin: I take nouns and adjectives and use them as verbs. Remember when ‘access’ was a thing? Now it’s something you do. It got verbed.”

— Bill Watterson, “Calvin and Hobbes” (1993)

Oxymoron: a rhetorical form wherein contradictions are juxtaposed.

“And whispered in the sound of silence.”

— Paul Simon & Art Garfunkel, “The Sound of Silence” (1964)

“Parting is such sweet sorrow.”

— William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (1595)

Irony: a rhetorical form wherein the words run contrary to the true meaning.

“It is forbidden to kill; therefore all murderers are punished unless they kill in large numbers and to the sound of trumpets.”

— Voltaire, Questions sur l'Encyclopédie (1774)

“War is peace. Freedom is slavery. Ignorance is strength.”

— George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949)

Ronald T. Kellogg, The Psychology of Writing (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 8.

Edward P. J. Corbett, Classical Rhetoric for the Modern Student (New York: Oxford University Press, 1965), 536.

Gideon O. Burton, “Content/Form,” Silva Rhetoricae. http://rhetoric.byu.edu.

Francis Yates, The Art of Memory (New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966), 368.

Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 298.

Masterful

Everybody rapping like it's a commercial

Actin' like life is a big commercial

-- Michael Diamond, "Pass the Mic" (1992)