To Write Like Hemingway: Part I | Hard to Kill

Part I of III

When you start to write everybody is wishing you luck, but when you’re going good, they try to kill you.

— Ernest Hemingway, 19341

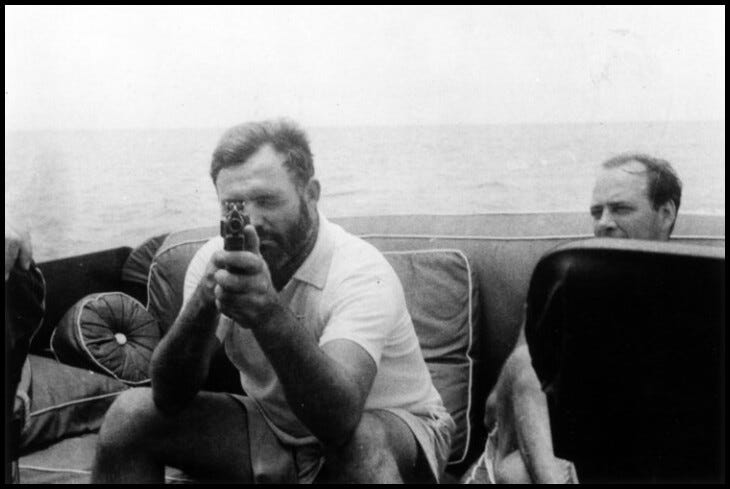

In July of 1918, somewhere along the Italian front at Fossalta di Piave, an Austrian trench-mortar bomb exploded in the darkness, blowing the legs off three Italian soldiers and hospitalizing an 18-year-old Ernest Hemingway.

“I died then,” Hemingway later wrote, “I felt my soul or something coming right out of my body, like you’d pull a silk handkerchief out of a pocket by one corner. It flew around and then came back and went in again and I wasn’t dead anymore.”2

In October of 1954, Hemingway was forced to accept the Nobel Prize in Literature in absentia due to injuries from, not one, but two plane crashes in East Africa earlier that year.

Hard to kill.

On the literary front, however, the survival of Ernest Hemingway is more miraculous still. An avid boxer and hunter, no respect for academia or elites, no time for politics or schmoozing, a lover of booze, feuds and four-letter words, all canalized through a blue-collar prose and brash persona… Far from the archetype, Hemingway was perhaps the antonym of a “critical darling.”

Indeed, as early as 1930, notes Edmund Wilson, Hemingway had already become fashionable to hate—not amongst writers and readers, of course, but amongst the literati; critics, academics, et al.3

Truth be told, he gave many good reason.

In 2023, little has changed. His name, when cited at all, often serves as little more than a counterpoint to the elegance and eloquence of a Faulkner or Fitzgerald. When given a full article, one can usually count down the sentences until analysis of his prose turns to psychoanalysis of his personality or, more accurately, his persona—a mythologized persona, largely, whose embers Hemingway (happy to be regarded as a literary bro) and his haters (happy to regard him as such) were both happy to inflame.

Yet, throughout a hundred-year siege on his place within the canon—a siege that has swallowed the memory of countless literary assassins, outlasted the arcs of countless critical darlings—Hemingway lives on; scathed, but very much alive. Antifragile.

Hard to kill.

It is a longevity unlike many others, perhaps any other, for Hemingway has not survived because of the literary establishment, but rather despite of it. From early on, Hemingway took his legacy into his own hands, leaving nothing to chance and even less to critics, cementing his status as a great—as one of the greats—without permission. Which brings us to the real question:

How do we, like Ernest, become hard to kill?

The answer will take the form of three parts:

I. Hard to Kill, II. The Craftsman, III. Polymathematics.

Each part will be explored, not through the eyes of a sociologist, but through those of a writer; someone hellbent on becoming better; someone, as Hemingway was, hellbent on beating the competition.

Arnold Samuelson, With Hemingway: A Year in Key West and Cuba (New York: Random House, 1984), 34.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949.

Tom Stoppard, “Reflections on Ernest Hemingway” in Ernest Hemingway: The Writer in Context, ed. James Nagel (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 19.

Top notch essay, Dylan. Will be watching my inbox for future instalments.

Well done. Interesting commentary and got me thinking critically about writing. Looking forward to more.