To Write Like Hemingway: Part II | The Craftsman

Part II of III

Dostoevsky was made by being sent to Siberia. Writers are forged in injustice as a sword is forged.

— Ernest Hemingway, Green Hills of Africa (1935)

I. The Craftsman

The mythos of Ernest Hemingway, a problem child, a playboy of the Western world, tells less than half the story of the man. “He was not a born sportsman who somehow learned how to write,” Malcolm Cowley once observed. “On the contrary, he was a born writer and student who taught himself painfully how to be a sportsman.”1

Behind the bravado, closed off from paparazzi and literati of his time and ours, Hemingway lived the life of a craftsman; a life closer to carpentry than culture, largely composed of solitude and quiet.

For Hemingway, writing was less a profession than a trade; something that demanded the hand as much as the head; something that demanded apprenticeship before mastery; something that, done right, demanded the discipline of a soldier and the dedication of a priest. “That’s all there is to writing,” he wrote, “the devotion to your work and respect for it that a priest of God has for his, and then have the guts of a burglar, no conscience except to writing, and you’re in, gentlemen.”2

Despite his guts and conscience, however, Hemingway paid a great price for greatness. From an early age, the irreducible conflict between writing and living cut through his heart in Solzhenitsyn fashion. “It was hard to be a great writer if you loved the world and living in it,” Hemingway lamented.3 “A life of action is much easier to me than writing… Writing is something that you can never do as well as it can be done.”4

Yet, do he did. Often to the detriment of action, adventure, friendships, and romance, Hemingway fastened his very being to the craft of writing, charting a course through the terra incognita of style and substance, seeking neither solace nor shortcuts along the way. “Organizations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing,” he wrote, accepting the Nobel Prize.5 “The further you go in writing the more alone you are.”6

What John, Paul, George and Ringo did in Hamburg, Hemingway did alone. 10,000 hours of solitude, come rain or shine. “There is nothing to writing,” he wrote, touching upon the hope and despair of greatness. “All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.”7 There were no shortcuts, no hacks. Immortality was a mountain that, without ritual, without sacrifice, one could never hope to climb.

As I said, less than half the story.

II. Mornings

“Write drunk, edit sober.” It turns out the most popular Hemingwayism of all is not a Hemingwayism at all, but the mantra of a close friend, F. Scott Fitzgerald. In fact, true craftsman as he was, Hemingway never wrote nor edited drunk, but rather used alcohol as a means of marking the end of a good day’s writing: a carrot, not a crutch.

Religiously, hungover or not, Hemingway wrote in the morning: “I’ve seen every sunrise of my life” being one of his favourite refrains.8 In his younger days, Hemingway would try to be at his desk soon after 6 o’clock, though the starting pistol sounded closer to 8 o’clock later in life.

Contrary to popular lore, Hemingway did not begin each morning with the ritual of sharpening twenty pencils. “I don’t think I ever owned twenty pencils at one time,” he told Paris Review.9 “Wearing down seven No. 2 pencils is a good day’s work.”10 Rather, before putting pencil to paper, Hemingway would begin each morning by reading over what he had written thus far—the whole novel, until he reached the halfway point, and then two or three chapters thereafter.11

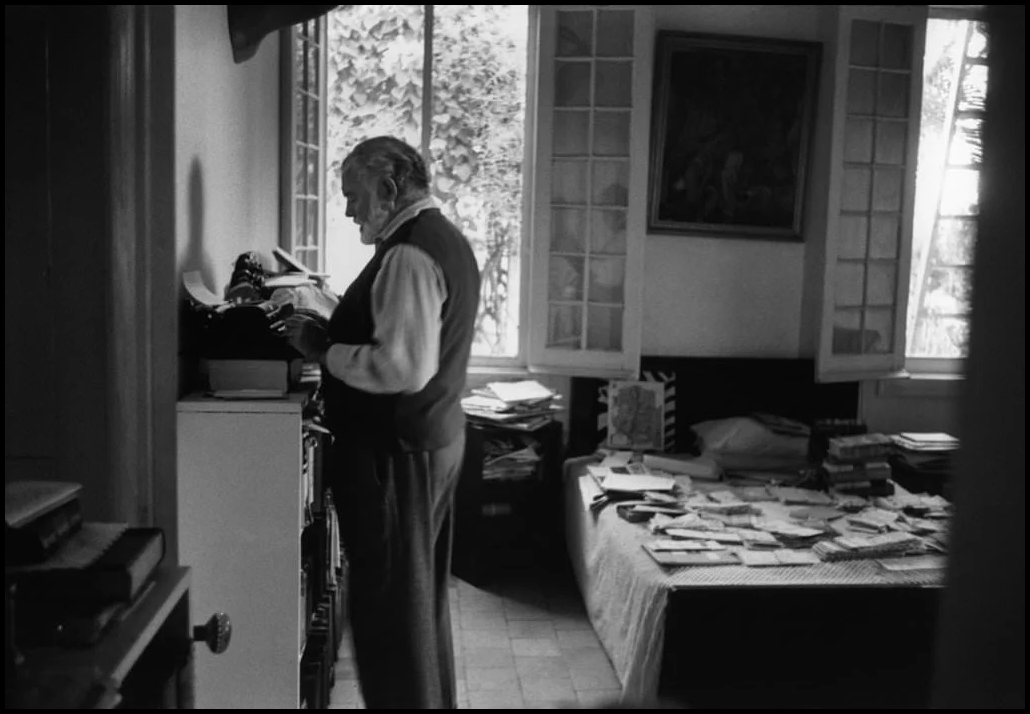

From the very beginning—again, reminiscent of true craftsmanship—Hemingway stood when he wrote. His notebook, typewriter, and reading board at chest-height on a bureau or bookshelf opposite him; a working dynamic beautifully captured by Malcolm Cowley below.

III. Process

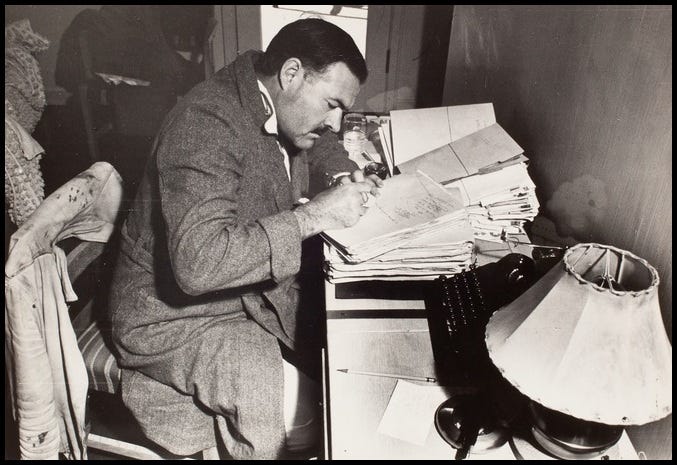

For Hemingway, first drafts never began with the typewriter, always the pencil. Placing sheets of onionskin typewriter paper slantwise across his reading board, Hemingway would lean against the board with his left arm, steadying the paper his left hand, before letting his right hand get to work.12

The size of his handwriting varied greatly, from the Lilliputian to the boyishly large, often resulting in as few as nineteen lines per page.13 Pace was vital, leaving little time for punctuation or capital letters.14 Though everything moved fast—during first drafts, especially—dialogue moved the quickest, with Hemingway once noting that when he got four people talking everything flowed like a dream.15

In terms of “pre-paper discipline,” something that John O’Hara argues distinguished the likes of Hemingway and Steinbeck from the rest of the pack, Ernest was an advocate of forethought, though an enemy of outlines.16

Instead, as Malcolm Cowley describes, Hemingway approached his stories like an exploring expedition setting out into unknown territory, terra incognita: “He knows his approximate goal, but the goal can change. He knows his direction, but he does not know how far he will travel or what he will find on a given day’s journey.”17

“The process of adding and subtracting is done on a different esthetic plane,” writes Robert W. Lewis, “and intentionality must ordinarily be more operative in the cooler process of revision than in the initial hard groping toward ends of chapters and sentences.”18 It was only when the writing was going well—when there were words to work with—that the typewriter entered the fray.

Chapters, too, came later. But when they came, as the heat of composition dissipated and cooler processes prevailed, they came with the cold-blooded and steady-handed precision of a surgeon. In a beautiful essay entitled “Last Words,” Joan Didion excerpts a letter Hemingway sent to his publisher in early 1961, which rather well encapsulates the true scope of his craftsmanship, from the brash to the punctilious:

Have material arranged as chapters—they come to 18—and am working on the last one—No 19—also working on title. This is very difficult. (Have my usual long list—something wrong with all of them but am working toward it—Paris has been used so often it blights anything.) In pages typed they run 7, 14, 5, 6, 9 1/2, 6, 11, 9, 8, 9, 4 1/2, 3, 1/2, 8, 10 1/2, 14 1/2, 38 1/2, 10, 3, 3: 177 pages + 5 1/2 pages + 1 1/4 pages.19

IV. Afternoons

Calculating was not limited to chapters either. On the bureau or desk, beside the typewriter and reading board, Hemingway kept a large chart—scrawled on the side of piece of cardboard—so as to keep track of his daily progress, “so as not to kid myself.”20

“In one fairly typical week,” Cowley reports, “he wrote 485 words on Monday, 516 on Tuesday, 638 on Wednesday, 912 on Thursday and 276 on Friday, making a total of 2,827 for the week.”21 True to form, the most prolific days tended to constitute premeditated attempts to stave off the guilt of the following day’s fishing or drinking.

In stark contrast to the culture du jour, however, Hemingway was no productivity guru.

For Hemingway, in more ways than one, longevity—lasting—was the aim of the game. It was a lesson that Hemingway learned during the six-week fever dream of his first novel, The Sun Also Rises, which he “wrote too fast and each day to the point of complete exhaustion.”22

Flow—from minute to minute, day to day—was paramount.

So concerned was Hemingway with flow that he rarely ended a page by ending a sentence, but rather tended to stop himself—mid-flight—before grabbing a new page and continuing the sentence there.23 In fact, during his first drafts, Hemingway rarely ended a sentence at all, often marking an ‘x’ instead of a full stop, so as to never bring his pencil to a halt.24

Interestingly, though born of intuition, Hemingway’s insight has been borne out by data. In studying the mechanics of task completion, researchers have discovered a phenomenon that has come to be known as “the Hemingway effect,” whereby those who purposefully interrupted the completion of a task not only experienced better recall, but exhibited better rates of completion.25

Quantitatively as well as qualitatively, Hemingway lives on.

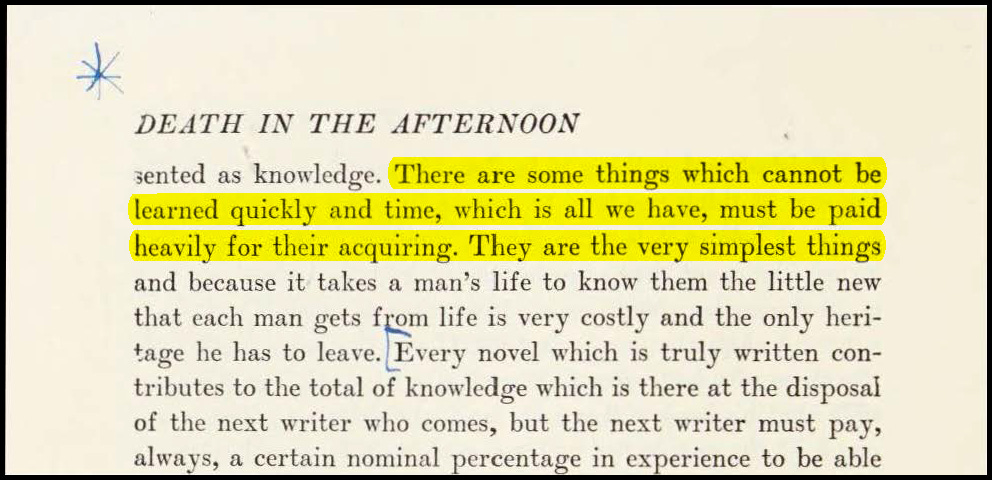

V. The Craft

Nobody becomes as hard to kill as Hemingway by happenstance alone. By way of his devotion to the craft, Hemingway became undeniable, leaving a legacy that neither his critics nor his competition have managed to rearview.

Yet, perhaps the greatest source of Hemingway’s antifragility stems not from his mastery per se, but his denial of it. “I’m apprenticed out at it until I die,” he wrote, later in life. “Dopes can say you mastered it. But I know nobody ever mastered it, nor could not have been better.”26 It is a sentiment that touches upon the true spirit of craftsmanship: a lifelong pursuit, for which no life is long enough.

On this point, there is little I can say better than the man himself, so I’ll bring things to a close with a quote that should first strike the aspiring writer with a sinking feeling of despair, but then counter with an even greater feeling of punchdrunk hope.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 96.

Ernest Hemingway, “The Art of the Short Story,” Paris Review, Vol. 79 (1981). https://www.theparisreview.org/letters-essays/3267/the-art-of-the-short-story-ernest-hemingway.

Ernest Hemingway, “On Writing” in Ernest Hemingway, The Nick Adams Stories (New York: Scriber, 1972), 238.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in Robert Paul Lamb, The Hemingway Short Story: A Study in Craft for Writers and Readers (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2013), 167.

Ernest Hemingway, “Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech”: quoted in Carlos Baker, Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972), 339.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in R. Andrew Wilson, Write Like Hemingway (Avon: Adams Media, 2009), 35.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in Clancy Signal, Hemingway Lives! Why Reading Ernest Hemingway Matters Today (New York: OR Books, 2013), 8.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in William E. H. Meyer, Jr., “Faulkner, Hemingway, et al.: The Emersonian Test of American Authorship,” The Mississippi Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 3 (1998), 38.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in Mason Currey, Daily Rituals: How Artists Work (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013), 52.

Ernest Hemingway: quoted in Carlos Baker ed., Hemingway and His Critics (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 23.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 100.

Carlos Baker, “Introduction: Citizen of the World” in Hemingway and His Critics, ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 20.

Robert W. Lewis, “The Making of Death in the Afternoon” in Ernest Hemingway: The Writer in Context, ed. James Nagel (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 35.

Carlos Baker, “Introduction: Citizen of the World” in Hemingway and His Critics, ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 20.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 101.

John O’Hara, “The Author’s Name Is Hemingway,” The New York Times, 10 September 1950. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/99/07/04/specials/hemingway-river.html.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 100.

Robert W. Lewis, “The Making of Death in the Afternoon” in Ernest Hemingway: The Writer in Context, ed. James Nagel (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 39.

Joan Didion, “Last Words: Those Hemingway Wrote, and Those He Didn’t,” The New Yorker, 25 October 1998. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/11/09/last-words-6.

Carlos Baker, “Introduction: Citizen of the World” in Hemingway and His Critics, ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 20.

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 100.

Carlos Baker, Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972), 75.

Peter Elbow, Writing with Power (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 14.

Carlos Baker, “Introduction: Citizen of the World” in Hemingway and His Critics, ed. Carlos Baker (New York: Hill and Wang, 1961), 20.

Yoshinori Oyama, Emmanuel Manalo & Yoshihide Nakatani, “The Hemingway Effect: How Failing to Finish a Task Can Have a Positive Effect on Motivation,” Thinking Skills and Creativity, Vol. 30 (2018).

Malcolm Cowley, “A Portrait of Mister Papa,” Life Magazine, 10 January 1949, 101.

Great compilation and weaving of quotes here. The last Hemingway quote sounds a lot like Orwell from (if I'm not mistaken) WHY I WRITE: "Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout with some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand."

AMAZING!!!