To Write Like Hemingway: Part III | Polymathematics

Part III of III

“The hardest thing in the world to do is to write straight honest prose on human beings.

First you have to know the subject; then you have to know how to write.

Both take a lifetime to learn and anybody is cheating who takes politics as a way out.

It is too easy.”

— Ernest Hemingway, “Old Newsman Writes: A Letter from Cuba” (1934)1

I. The Polymath

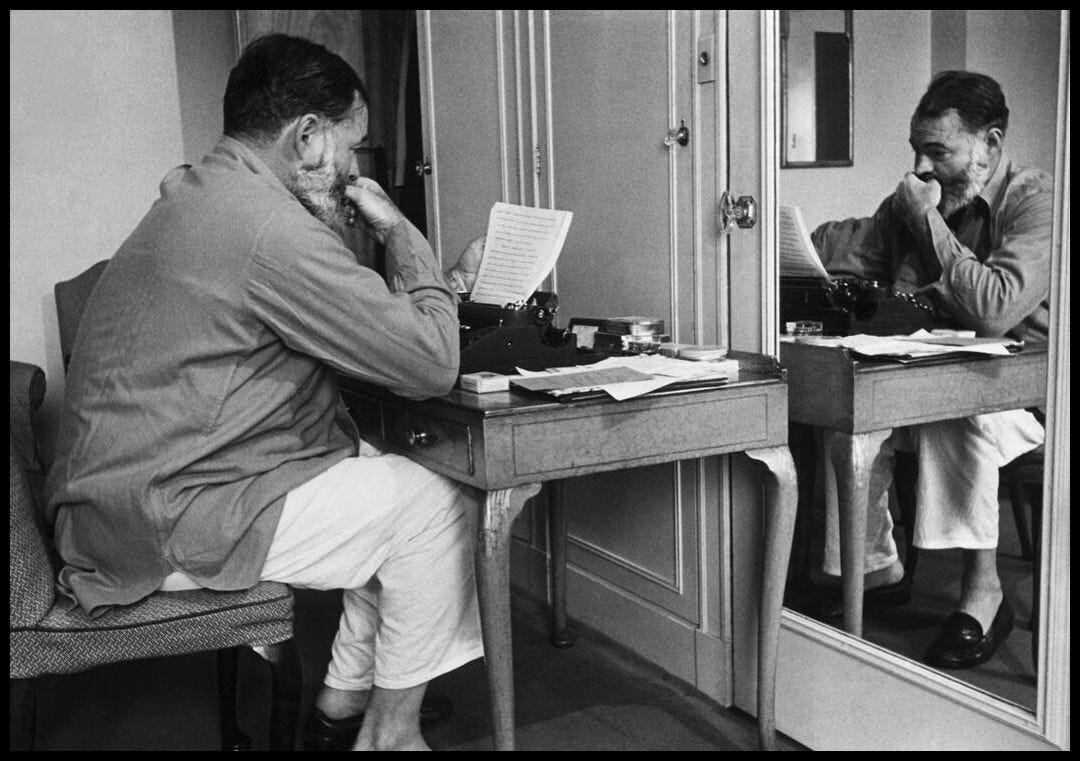

Unlike Whitman, Hemingway did not so much contain multitudes as depths, dimensions. He did not lead the double or triple life of a Leonardo da Vinci or Lewis Carroll, artistically speaking, but rather a singular life, sharpened to a knifepoint. Yet, despite his singularity, his monogamous devotion to the ultimate end of writing and writing alone, Hemingway was—as all true artists are—polyamorous with his means.

Painters, poets, composers, explorers: quite the tapestry of influence for a writer often regarded as one-dimensional. At first glance, to be fair, Hemingway can evoke a feeling of flatness. The words are simple; the sentences, spare. Yet, contrary to approaching a figure in the distance, the closer one gets to Hemingwayian prose, the less clear things become; the less black and white the pages appear. Shadows arise, chasms open; fourth, fifth dimensions come to light.

II. The Reporter

Born into a world of gunsmoke and propaganda, Hemingway was no stranger to the limitations of language. From his vantage point as a war correspondent, Hemingway had witnessed Europe become a hollow abstraction of its former self: a rhetorical wasteland, ruined by the ideologues and intellectuals of the hour.

How does one write fiction in such a world? A world already false, already full of half-truths and glaring lies? The answer, to Hemingway, was simple—was simplicity.

“Go in fear of abstractions,” wrote Ezra Pound, an early mentor of Hemingway’s. “The subject is always interesting enough without the blankets.”23 So, abandoning the zeitgeist and returning to the first principles of his apprenticeship at the Kansas City Star, Hemingway went—a disaffected soul in search of solid ground.

Simple words, simply arranged. That was Hemingway, always striving to get language out of the way—a writer for whom prose was architecture, not interior decoration.4 His style embodied that of a veteran reporter, full of places, names, and faces, forever suspicious of adverbs, adjectives, all things second-hand. It was a style “in which the body talks rather than the mind,” wrote Cyril Connolly—a style very much antithetical to the litterateurs of his day.5

“He has no courage, has never climbed out on a limb,” wrote Faulkner, a lifelong rival. “He has never used a word where the reader might check his usage by a dictionary.”6 With his reply, Hemingway was classically pointblank:

Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.7

Beneath Hemingway’s lack of madness, however, was a method. For to champion the simplest words was, as a general rule, to champion the oldest words, the sturdiest words; language tried, tested, and true, impervious to the changing winds.

Antifragile.

III. The Architect

Indeed, beyond language, Hemingway was always striving to get himself out of the way. Prose was architecture, remember: an artform in which the building, not the builder, takes centre stage.

After an evening spent walking around La Sagrada Familia, one does not come away with a biography of Antoni Gaudí. One feels no need for critical theory, no desire for secondary literature. The beauty of the cathedral stands alone; stands apart from the Heraclitean flux of life and language. A timeless way of building, as Christopher Alexander would say.

That is the standard to which Hemingway not only held himself, but his literary heroes. “I love War and Peace for the wonderful, penetrating, and true descriptions of war and of people but I have never believed in the great Count’s thinking,” Hemingway wrote:

I wish there could have been someone in his confidence with authority to remove his heaviest and worst thinking and keep him simply inventing truly. He could invent more with more insight and truth than anyone who ever lived. But his ponderous and Messianic thinking was no better than many another evangelical professor of history, and I learned from him to distrust my Thinking with a capital T and to try to write as truly, as straightly, as objectively and as humbly as possible.8

As architecture was to Gaudí, literature was to Hemingway: an exercise in immortality. Popularity, in here and now, was but a battle. Longevity was the war. There were casualties, of course—experiential, egotistical—but in allowing the art to speak for itself, Gaudí and Hemingway allowed a higher form of objectivity to enter the fray, tilting the scales in favour of a death-defying escape from the quicksands of time.

IV. The Painter

In stripping his prose of pomp and ego, moreover, Hemingway achieved something remarkable with the remainder: a direct line between reality and the reader. “If beauty lies in the eye of the beholder,” observes Harry Levin, “Hemingway’s purpose is to make his readers beholders.”9

Indeed, upon first reading Hemingway, one quickly becomes aware that experience is not hierarchized, but rather laid out along a latitudinal plane, like the panning of camera or the turning of a head—an experience beautifully rendered in Sean O’Faolain’s reading of “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place.”

Herein lies the phenomenological force of Hemingway, a writer as much influenced by the paintbrush as the pen. “Hemingway said he learned how to describe scenery by studying Cézanne,” writes Russell Banks:

I learned how to describe scenery from reading Hemingway. Look at “Hills Like White Elephants” or almost anything. Look at the physical description, how he moves from background to foreground. It’s the logic of the eye. It’s not the logic of the paragraph. And it’s not the logic of exposition. It’s the logic of the eye.10

V. The Poet

Behind the eye, though, Hemingwayian prose takes on another dimension still: a poetic dimension, which—like an optical illusion—brings the whiteness of the page rushing to the fore.

In 1922, en route home from reporting on Greco-Turkish War, a suitcase containing nearly all of Hemingway’s manuscripts was stolen at a Paris train station. It was a fortunate loss, ultimately, for during that painful divorce from his work, Hemingway formulated his Theory of Omission—which is to say, his Iceberg.

It is with the suggestiveness of a poet that Hemingway leads the reader through his prose, swerving between the black and the white, the spoken and the silent, the surface and the deep, oftentimes dragging us headlong toward the point of contact, before—in true matador fashion— deftly stepping out of the way.

Poetry in motion.

VI. The Mathematician

It is at this juncture between poetry and prose that we arrive—finally, and rather unexpectedly—at mathematics.

“He once told me he was working in a new mathematics, and I was skeptical,” wrote Harvey Breit, the morning after the tragedy:

I thought that even great and simple men delude themselves. But it turned out he was working in it. He had staked out a unique terrain.11

Indeed, upon rereading Hemingway, one can retrace his steps right back to the very beginning.

And yet, while the true nature of his mathematics will never be known, one could argue that the very existence of this essay (and your e to read this far) lends some credence to his claims. For in truth, a century later, very little has gone bad. Much like La Sagrada Familia, whose architecture remains unrivaled, inimitable, Hemingway’s prose stands up and stands alone.

Perhaps not evidence of any fourth or fifth dimension in the field of mathematics, but evidence of a language that escaped the grasp of space and time?

I’m certainly not alone in thinking so.

“One of the bravest and best, the strictest in principles, the severest of craftsmen, undeviating in his dedication to his craft. He is not dead. Generations not yet born of young men and women who want to write will refute that word as applied to him.”12

— William Faulkner

“Hemingway continues to be where one least expects to find him—20 years after his death.”13

— Gabriel García Márquez

“He has had the most profound effect on writing—more than anyone I can think of.”14

— John Steinbeck

“While one can do nothing about choosing one’s relatives, one can, as artist, choose one’s ‘ancestors.’ … Hemingway was an ‘ancestor.’”15

— Ralph Ellison

“For the past thirty years Hemingway, stylistically speaking, has influenced more writers on a world scale than anyone else.”16

— Truman Capote

“I always say Hemingway, because he taught me how sentences worked. When I was fifteen or sixteen I would type out his stories to learn how the sentences worked… I mean they're perfect sentences. Very direct sentences, smooth rivers, clear water over granite, no sinkholes.”17

— Joan Didion

“Wherever you go, whether in India, the Middle East or elsewhere, you find that the young writers have read his short stories and are trying to imitate him.”18

— V. S. Pritchett

“Not a living writer in England who has been unaffected by the laconic speed of his dialogue, the subtle revelation of character that lies behind a spoken phrase.”19

— Alan Pryce-Jones

“Hemingway’s influence on the matter of recent Japanese writing is beyond question. Japan is among his most loyal realms.”20

— Edward Seidensticker

“Spain no longer looks down on powerful America as a nation of meat packers without history. She has learned to respect and admire the nation that gave Ernest Hemingway to the world.”21

— Salvador de Madariaga

Ernest Hemingway, “Old Newsman Writes: A Letter from Cuba” in By-Line: Ernest Hemingway, ed. William White (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1967), 183.

Floyd C. Watkins, The Flesh and the Sword (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1971), 100.

R. Andrew Wilson, Write Like Hemingway (Avon: Adams Media, 2009), 35.

Ernest Hemingway, On Writing (New York: Touchstone, 1984), 74-75.

Cyril Connolly, Enemies of Promise (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1949), 65.

William Cane, Write Like the Masters: Emulating the Best of Hemingway, Faulkner, Salinger, and Others (Cincinnati: Writer’s Digest, 2009). 133.

A. E. Hotchner, Papa Hemingway: A Personal Memoir (New York: Random House, 1966), 69-70.

Carlos Baker, Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972), 199.

Harry Levin, “Observations on the Style of Ernest Hemingway” in Hemingway: A Collection of Critical Essays, ed. Robert P. Weeks (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1962), 81.

Steve Paul, “On Hemingway and His Influence: Conversations with Writers,” The Hemingway Review, 22 March 1999.

The New York Times, “Authors and Critics Appraise Works,” The New York Times, 3 July 1961. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/99/07/04/specials/hemingway-obit4.html.

Ibid.

Gabriel García Márquez, “Gabriel García Márquez Meets Ernest Hemingway,” The New York Times, 26 July 1981. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/99/07/04/specials/hemingway-marquez.html.

The New York Times, “Authors and Critics Appraise Works.”

Robert Paul Lamb, “Hemingway and the Creation of Twentieth-Century Dialogue,” Twentieth Century Literature, Vol. 42, No. 4 (1996), 453.

The New York Times, “Authors and Critics Appraise Works.”

Linda Kuehl, “Joan Didion, The Art of Fiction No. 71,” The Paris Review, No. 74 (1978).

The New York Times, “Authors and Critics Appraise Works.”

Ibid.

Robert Paul Lamb, Art Matters: Hemingway, Craft, and the Creation of the Modern Short Story (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010), 3.

Ibid.

Great piece, Dylan. You said it all, and said it well. Simple things are often the hardest things to do well, and to do distinctly. Hemingway did the simple things extraordinarily well.

Love this series! Go Dylan!